12+ In February 1998, I started an eight-week evening college course, Introduction to Philosophy. I was in my mid-thirties, and while I was aware of philosophers, I hadn't read their works and knew nothing about critical thinking. Our text was Sophie's World by Jostein Gaarder. And our tutor was a Marxist.

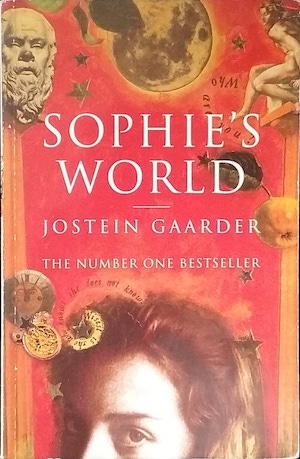

Published in 1995, Sophie's World is the bestseller novel about the history of philosophy. It opens with Sophie, a fourteen-year-old schoolgirl, finding two pieces of paper in her mailbox with two questions:

- Who are you?

- Where does the world come from?

The novel takes Sophie and the reader on a tour of Western Philosophy, from the pre-Socratics to 20th-century philosophers, as she seeks answers to these existential questions.

Each week our tutor set chapters from the novel as homework, and in the following class, he facilitated discussions and debates over what we'd read. It proved a steep learning curve, as I observed in a diary entry dated 17th February:

Just managed to hold onto the thread of this evening's class by a thin strand. Others fared less well, admitting afterwards to complete confusion.

But I liked reading Sophie's World and the weekly stimulation of the philosophy classes, even if I often went home with a thrumming headache.

A Marxist Rant

And then, in late March, the tutor skipped over the section he'd told us to read during the week to a chapter on Marx, and suddenly the class felt different. There was no interactive discussion; it was old-fashioned chalk-and-talk. And the tutor was so passionate about Marx and Marxism that a fellow class member later described the lesson as a "rant".

I wasn't surprised to find empty seats in the philosophy class the following week. And I regretted not staying home, too, when the tutor started the lesson where he'd left off on the topic of Marxism and "workers' consciousness". Thankfully, after a short rant, he returned to the chronology of Sophie's World, and we moved on to Freud, which seemed fitting.

When the course finished in early April, I joined a handful of stalwarts — who, like me, had attended all the classes — for a farewell dinner with the tutor. My diary entry for 14th April records we didn't talk about philosophy, but we did discuss a letter of complaint sent to the evening college after the Marxist-rant lesson:

"I wish to make an official and strong complaint about the course, Introduction to Philosophy, and the class tutor. This course is being used for political purposes. In March, the tutor deviated from the course structure to devote an entire lesson on Marx. He then admitted he is a Marxist and therefore teaches philosophy from a Marxist perspective. In my opinion, he is using this course as a vehicle to promote his own political ideology."

This is only a short extract from a three-page letter documenting dates, perceived deviations, and the heated after-class debate between the class member — who stopped attending lessons after the Marx night — and the tutor. We all remembered the complainant class member: he'd been an intense guy, prone to pushing his point of view, and had veered outside the course structure himself on several occasions.

Not to be outdone, the tutor responded with a five-page letter, which he also shared with us. It was an exhaustive point-by-point rebuttal of the complainant's assertions and a detailed defence of the course, its methods and objectives. The tutor concluded:

"I maintain my right to discuss critically the views of any philosopher. My perspective and the perspectives of the various philosophers discussed throughout the course were publically declared. Some of the stated aims of the course are to develop the abilities to see others' points of view, explore other possibilities, engage in self-correction, maintain relevance, and make considered judgements. From his letter and behaviour during sessions, it appears the complainant has not gained any of these abilities."

My fellow stalwarts and I felt the complaint was over the top. Yes, the Marx lesson wasn't our favourite class. But as I commented in my diary that night, the disgruntled class member accused the tutor of being "a card-carrying Communist intent on converting us to Marxism".

In the end, I offered to write a letter of support for the tutor and course. I couldn't match the passion or eloquence of either party in the dispute, so mine was only a one-pager. First, however, I felt I had to address the Marx evening:

"I too had concerns over the Marx lesson, and I discussed these with another class member. We both agreed the content wasn't the problem, but how it was presented. Previous classes were interactive, encouraging discussion, while this class was more a traditional chalk-and-talk, sit and listen to the teacher session."

But I closed my letter with a compliment:

"The philosophy course proved difficult, stimulating and informative. I would recommend it to anyone wanting a learning environment in which philosophical and personal viewpoints are explored and challenged".

An Alternative Method for Marx

I don't know how the evening college mediated the complaint. But the tutor and I shared two further items of correspondence, faxes (more common than emails in 1998). He acknowledged my letter's "critique of the epistemological chalk-and-talk fest during the Marx lesson" and asked if I had any thoughts on an alternative method for Marxism. I replied:

"Do what you did in the first lessons: get the class to discuss the issues and let the conclusions surface on their own accord. And perhaps it would be a good idea to separate Marx's theory on the development of knowledge from Marxism and Communism. Especially as we've come to know them from the despotic excesses of the 20th century."

LOVE WRITING NONFICTION?

Share and showcase your nonfiction and other writing — fiction and reviews — as a Guest Writer on Tall And True.

That was my first and last philosophy course. But I maintained an interest in the subject, read more widely on it, and nowadays subscribe to philosophy podcasts. And I finished and enjoyed Sophie's World.

As for the questions posed to her: who are you, and where does the world come from? Sophie and I worked through the book together and learned the answers. Admittedly, they weren't what either of us expected. But neither was my Marxist philosophy class.

© 2019, 2022 Robert Fairhead

N.B. You can listen to My Marxist Philosophy Class on the Tall And True Short Reads podcast. And you might like to read about My First Buddhist Lesson on Tall And True.

I shared My Marxist Philosophy Class on Tall And True after finding the fax communication between the course tutor and myself in a box of papers in September 2019.

I enjoyed drawing on extracts from our faxes and my 1998 diary entries to craft the post. And I loved reacquainting myself with the story of Sophie's World by Jostein Gaarder.

What struck me most when writing the blog post was that although it was over twenty years since my Marxist philosophy class, the memories and emotions of that night were still vivid. And I guess this partly explains the passions of the class member who complained about the course and the tutor who defended it. And why Marx and Marxism still provoke passionate debate!

Robert is a writer and editor at Tall And True and blogs on his eponymous website, RobertFairhead.com. He also writes and narrates episodes for the Tall And True Short Reads storytelling podcast, featuring his short stories, blog posts and other writing from Tall And True.

Robert's book reviews and other writing have appeared in print and online media. In 2020, he published his début collection of short stories, Both Sides of the Story. In 2021, Robert published his first twelve short stories for the Furious Fiction writing competition, Twelve Furious Months, and in 2022, his second collection of Furious Fictions, Twelve More Furious Months. And in 2023, he published an anthology of his microfiction, Tall And True Microfiction.

Besides writing, Robert's favourite pastimes include reading, watching Aussie Rules football with his son and walking his dog.

He has also enjoyed a one-night stand as a stand-up comic.

Browse & Buy on Amazon.com.au

Browse & Buy on Amazon.com.au